How the Gospel Crosses Cultures

Missiological Theology Part 2: The "Where" of Missiological Theology

As I work on the literature review for my dissertation, I am examining Missiological Theology as a framework indigenous expressions of church as a movement. I will be posting reflections on my readings here, as a form of pre-writing. This post represents one in that series of reflections.

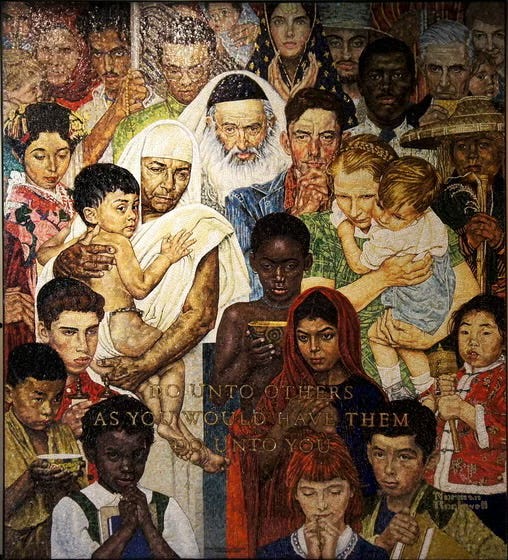

In the fifteenth chapter of Acts, a subtle shift took place that changed the trajectory of the church as a movement. It was of course a council between the leaders of the church in Jerusalem and those in Asia Minor. In the former, groups followed the politico religious structure of the Jewish synagogue.1 They attended the temple2 and their communal support for one another3 resembled the social welfare system of the synagogue.4 But the churches of Ephesus and other cities to the north were different. They were ethnically diverse, and more often than not, took on the characteristics of the Roman household, a voluntary association, or even a philosophical school.5

The council was called to discuss whether or not such churches should be made to observe Jewish Law in order to follow Christ. Perhaps they did not realize it at the time, but those present were really discussing whether or not the Jesus movement was capable of transcending cultural barriers. To require adherence to Jewish custom was to insist that new Christians disassociate themselves from their culture and become Jewish. The council ultimately decided against this, and in doing so made it possible for the Jesus movement to find a home in other cultures.

The rest of Luke’s account of the acts of the apostles explores the implications of the council. Churches proliferated across the ancient world and successfully found a home in Greco-Roman culture. The number of Christians in the Roman Empire then grew from around 25 thousand to as much as 20 million in just a little over 200 years.6 Surely, such exponential growth was due at least in part to the church’s ability to cross into new cultures.

But the world today is not like the Mediterranean of Paul’s time. The church’s long history in the West and association with the era of colonialism has reinterpreted the balance of power between cultures in terms of aggression.7 As previously stated, the colonial era of missions saw the church in the Majority World greatly impacted by Eurocentric worldviews.8 This has led missiologists to ask whether it might still be possible to recapture the ability of the church in Acts 15 to cross into diverse contexts.

Context is King

While it has been argued that any theology viewed as irrelevant is—in fact—irrelevant,9 the discourse around contextualization springs from “a growing awareness that [traditional Western] approaches [to theology] are not just irrelevant, but oppressive.”10

To the extent that theology is faith seeking understanding,11 Stephen Bevans argues that experience plays a central role in the act of seeking understanding. It is our experience of the past, in the forms of scripture and tradition that have often been thought to provide the raw materials for the creation of our theology. But Bevans says that our experience of the present—in the form of our current context—engages in dialogue with the past.12 This contextualization takes on a critical nature as current practices are “explicitly examined with regard to [their] meanings and functions in the society, and then evaluated in the light of biblical norms.”13

But what if the history our tradition is built upon has privileged one cultural context above others? What if those doing the work of theology have even benefited from the exploitation of those receiving it? As explored previously, it is even possible that natives will propagate Western cultural forms due to neo-colonial mimicry. Proponents of contextualization argue that great care should be taken when communicating the gospel across cultural barriers. Bevans summarizes six of the most common approaches to do so:

The Translation Model. The missionary identifies the core content of Christian belief and communicates it using native language and cultural concepts. The goal is not a word-for-word translation, but something more like the dynamic equivalence14 used in Bible translation.15

The Anthropological Model. The missionary or native believer places a high emphasis on the preservation of the culture and uses ethnographic and anthropological methods to better understand and reinterpret Christian belief accordingly.16

The Praxis Model. The missionary places an emphasis on the practice and outcome of a theology, conveying ideas to bring about social or systemic change. All liberation theologies may be considered a form of praxis contextualization.17

The Synthetic Model. The missionary attempts to combine other models of contextualization, namely the translation model and the praxis model. She may also insist on exploring the contextual theologies that have emerged in other cultures and maintain consistent dialogue with them.18

The Transcendental Model. The missionary seeks to engender a truly authentic faith experience in native believers. This is done by engaging the process of meaning-making as subjectively as possible, not only paying attention to overall culture, but the specific experiences of the specific subject in question.19

The Countercultural Model. The missionary regards the context as a hindrance to the objective and authoritative gospel. This model seeks a relevant engagement with culture by holding Christ over and against what may cause pain or distress to those living within the context.20

From Contextualization to Intercultural Theology

The colonial era, along with continued global patterns of migration since then, introduced new debates around multiculturalism. As countries around the world took on more immigrant populations, how should these different cultures relate to one another in a pluralistic society? To consider themselves a melting pot seemed to privilege one hegemonic culture above the others, expecting minority communities to simply assimilate. But the salad bowl metaphor contrarily undercut the unity of society at large, disparaging cultural mixing. For this reason, tha language of multiculturalism was abandoned for a language of interculturalism instead.21

William Dyrness reflects this intercultural way of thinking when he questions the language of contextualization:

I would argue that a new appreciation and appropriation of difference suggests that the language of contextualization needs fresh examination… Contextualization language, after all, has been developed and primarily directed at missionaries and evangelists who seek to communicate the gospel; now a variety of new actors have arisen that find this language inadequate.22

The “new actors” Dyrness speaks of are insider movements, but his argument can be applied to church planting and disciple making movements as well. For him, “the question now is not how do we go about placing the gospel in the culture, but rather, how do we respond, in light of scripture, to what God is already doing in a given culture?”23 Though culture is man-made, it is created with the raw materials of God’s creation, so he inevitably has an interest in it.24 For this reason, what Justin Martyr called the Logos spermatikos, or seeds of the Word are present in all cultures.25

Both foreign missionaries and cultural insiders can respond to the inherent goodness of what God is doing in a culture by engaging in irenic exchange that is dialogical, not dialectical.26 Instead of seeking to impart a superior knowledge, the privileged outsider is instead encouraged to create a hermeneutical space27 by inviting others into respectful and mutual engagement. For missionaries this might include a great deal of self-awareness as their foreign status often carries with it a social power that may not present itself at face value.28

This is not to say that contextualization does not attempt such mutual dialogue. Bevans himself attempts to avoid making any one theology normative when he famously states, “all theology is contextual theology.”29 He argues for a mutually critical dialogue,30 but the inherently evaluative language creates an unintended paternalism. If the gospel is to be contextualized, then it will always favor the culture from which it is given.

From Intercultural Theology to Missiological Theology

Michael Cooper closely aligns with Dyrness but prefers the language of missiological, rather than intercultural, theology.31 The shift may seem subtle, but it is one with several implications.

The first is that missiological theology uses theocentric language to encourage disciple making. While there is no disagreement between Dyrness and Cooper that the missionary’s task is “focused on understanding the particularities of a people group with a view to seeing how God is at work in those particularities,”32 Cooper describes this in terms of a missiological exegesis rather than getting unnecessarily bogged down in concepts from the social sciences like transoccidentalization.33 In practice, language highlighting the missiological nature of God captures the embodied and transmissive qualities of being and making disciples34 by keeping us focused on imitating the Trinity’s “self-sending on their mission to draw more nations, tribes, people, and languages to glorify God.”35

The second implication of using missiological language over intercultural is that it is inherently movement-driven. Cooper argues that much of contextualization’s language constitutes an “anachronism most fitting for contemporary missionary work,” but that speaking of “God’s divine activity of self-revelation more fittingly demonstrates the motus dei of missiological theology.”36 Motus Dei, Latin for movement of God, characterizes the attribute of God in Christ that understands Him in a constant state of “movement to redeem the nations back to himself.”37 Consequently, “missiological theology naturally makes the missional move to people by communicating never-changing divine truth… in ever-changing words… God would use today.”38 Essentially, missiological theology is what intercultural theology becomes when it is integrated with the motus dei.

Finally, while intercultural language is inherently more modern, missiological theology ensures faithful adherence to orthodox belief by appreciating the wider scope of the Christian movement throughout history. Dyrness’ hermeneutical space immediately recalls to mind Paul Hiebert’s hermeneutical community, meant to protect against uncritical acceptance of aberrant cultural forms by enshrining the priesthood of the believer.39 But Cooper reminds us that, while diversity in a group can steer it away from erroneous interpretations of scripture, it can still favor interpretations deemed most beneficial to itself. To ensure this doesn’t happen, in missiological theology, the “hermeneutical community is extended to the historic traditions passed down from the apostles through the centuries.”40

But how far back should the missiological theologian go in order to hold a modern community to a historically orthodox hermeneutic? After all, church history is replete with disagreement and schisms, some benign and other shockingly violent. It would seem that to introduce history into the hermeneutical community also introduces an element of historical editorialization. How missiological theology overcomes this will be the subject of the next article in the series.

Bruce Malina and John Pilch. Social Science Commentary on the Book of Acts. (Minneapolis, Minn: Fortress, 2008.) 194

Acts 2:46 (NIV)

Acts 4:32 (NIV)

Lee Levine, The Ancient Synagogue : The First Thousand Years. 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005) 396-398.

Wayne Meeks, The First Urban Christians : The Social World of the Apostle Paul (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983) 75-84.

Alan Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways : Reactivating Apostolic Movements (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016) 39.

Stephen Neill, A History of Christian Missions. 2nd ed. (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1986) 411.

Kwame Bediako, Theology and Identity: The Impact of Culture upon Christian Thought in the Second Century and in Modern Africa (Minneapolis, MN: 1517 Media, 1999) 236.

Charles H. Kraft, Christianity in Culture : A Study of Dynamic Biblical Theologizing in Cross-Cultural Perspective (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1979) 296.

Stephen B. Bevans, Essays in Contextual Theology (Boston, MA: Brill, 2018) 33

Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, trans. Thomas Williams (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2001), 1.

Bevans, Essays, 2-3.

Paul Hiebert, “Critical Contextualization,” Missiology: An International Review 12 no. 3, 287–296. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/009182968401200303.

Kraft, Christianity, 264.

Bevans, Essays, 8-10.

Ibid, 12-14.

Ibid, 16-18.

Ibid, 19-20.

Ibid, 22-24.

Ibid, 26-28.

Henning Wrogemann, Intercultural Theology, Vol 1 : Intercultural Hermeneutics (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016) 350-351.

William Dyrness, Insider Jesus : Theological Reflections on New Christian Movements (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016) ix-x.

Ibid, 40.

Ibid, 41.

Justin Martyr, The First and Second Apologies, trans. Leslie William Barnard (New York: Paulist Press, 1997), 43–44 (Second Apology 8).

Michael T. Cooper, “What I Learned about Christianity from the Druids : An Evangelical Encounter with a Contemporary Pagan Religion” Missiology: An International Review, 36 no. 2 (April 2008) 180.

Dyrness, Insider, ix.

Scott A. Moreau, Evvy Hay Campbell, and Sue Greener. Effective Intercultural Communication: A Christian Perspective. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014) 173-174.

Bevans, Essays, 30.

Ibid, 2.

Michael T. Cooper, Innovative Disruption, (forthcoming) 52.

Michael T. Cooper, Ephesiology: A Study of the Ephesian Movement (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2020) 85.

William A. Dyrness and Oscar García-Johnson, Theology without Borders : An Introduction to Global Conversations. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2015) 33.

Hirsch, The Forgotten, 184.

Cooper, Innovative, 19.

Ibid, 41.

Warrick Farah, “Introduction” in Motus Dei: The Movement of God to Disciple the Nations ed. Warrick Farah et al. (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2021) 19.

Ibid, 41-42.

Paul Hiebert, Anthropological Reflections on Missiological Issues (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2001) 100-101.

Cooper, Innovative, 51.