As I work on the literature review for my dissertation, I am examining Missiological Theology as a framework indigenous expressions of church as a movement. I will be posting reflections on my readings here, as a form of pre-writing. This post represents one in that series of reflections.

In her book, “A Flexible Faith,” Mennonite journalist Bonnie Kristian recounts a phenomenon all too familiar with my generation, the millennials. One grows up within a particular church and is taught that church’s interpretation of controversial issues, such as evolution vs. creationism. These youth then go off to college only to discover that they can no longer hold to their church’s stance on the subject, so they assume they cannot be a Christian anymore.1 She goes on to argue:

The core problem is that the faith that young people are taught in their churches and Christian schools is far too narrow to handle the complexities and ambiguities that characterize our pluralistic, information-intensive, postmodern world.2

We face a similar problem in missions. But instead of issues like creationism and evolution, we face questions of cultural forms and meanings and whether or not they are tenable with Christian belief. As missionaries, we may assume it best to merely teach those outside the church what we were taught at home. But, as Roland Allen warned, this runs the risk of replicating Western church divisions on foreign soil.3

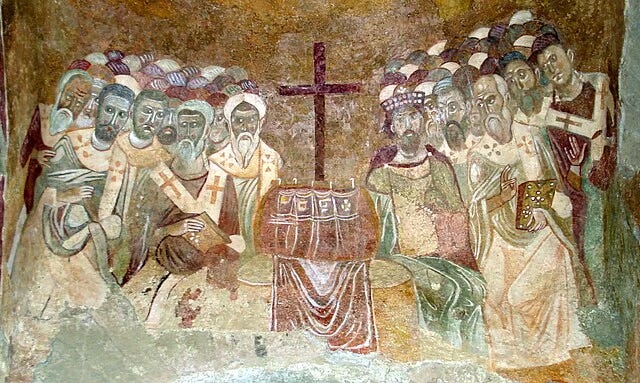

Missiological theology addresses both of these concerns by appealing to an ancient tradition passed down across generations. But the question remains, how far back should it go? As far back as the Great Awakening, an evangelical might argue. Or perhaps to the Protestant Reformation, says a Lutheran. Still other, more ancient churches may point to a synod or an ecumenical council. The problem is a fundamental one; What are the boundaries which constitute the Christian faith, which has disagreed so frequently throughout its long history?

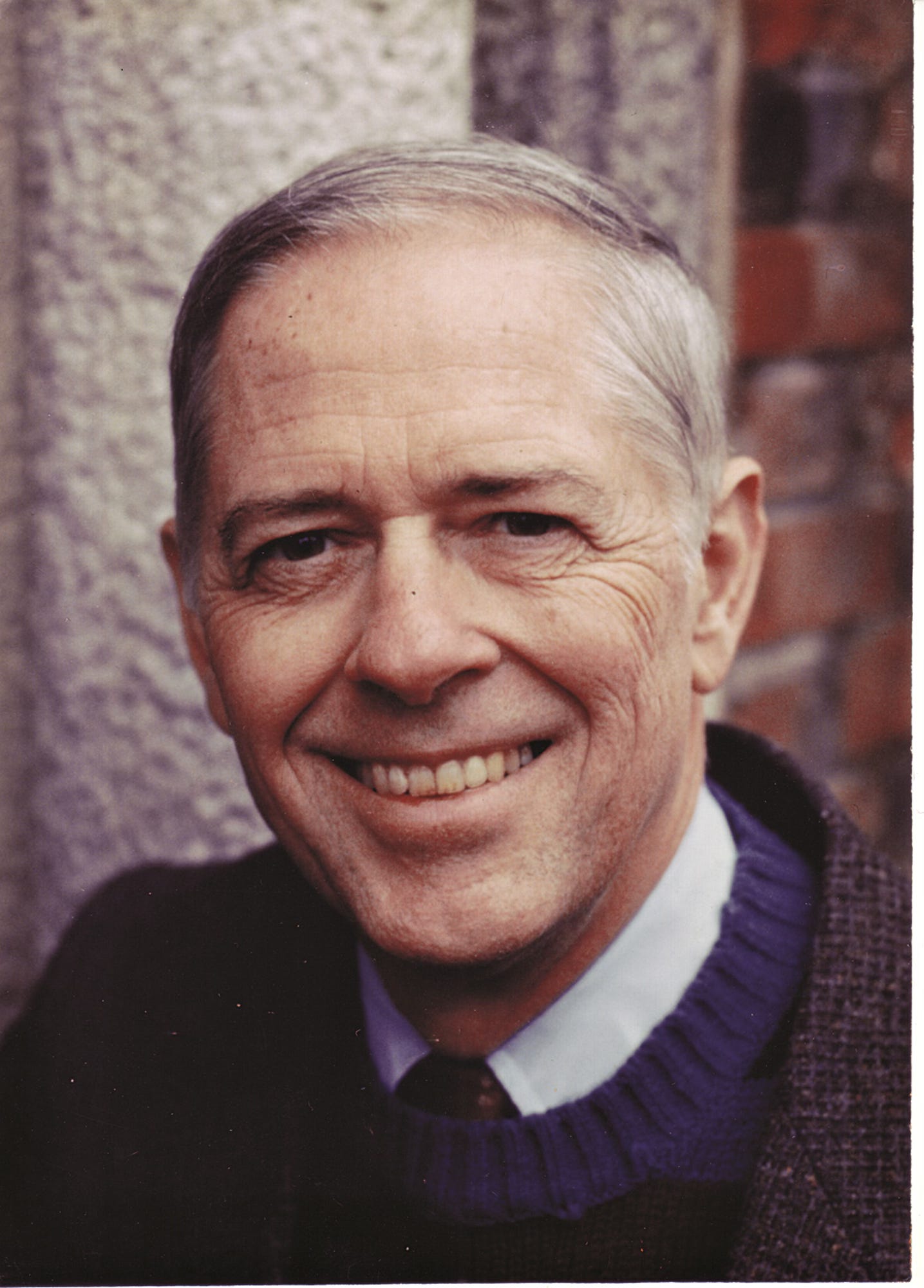

For his answer to this question, missiological theology owes a debt to theologian Thomas C. Oden, “who proposed that theology should not be looked at narrowly, but rather with boundaries… Those boundaries were initially set in the first five centuries of our faith.”4 To better understand Oden’s ideas, it is necessary to first examine a brief biographical account of his life.

A Change of Heart

Oden was like one of the young people Kristian wrote about in her book. Born in 1931, he experienced a peaceful, albeit humble childhood in Oklahoma’s Dust Bowl. At the age of ten, his life was upended by the Second World War. His application for military service denied due to health issues, his father moved the family to Oklahoma City to serve in the army’s recruitment office. After the war, Oden returned to his hometown of Atlus having experienced the loss of a cousin and the beginnings of a political imagination.5

During his undergraduate studies at the University of Oklahoma, Oden found himself drawn to atheist and agnostic scholars. At first he read them to test his belief system, but he soon found himself captivated by the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Karl Marx. By the time he attended seminary, he described himself as a “Marxist utopian dreamer.”6

In an attempt to reconcile his radical political beliefs with the Methodism of his youth, he had to demythologize his faith. For him the resurrection became a symbolic story, and “the gospel was not about an event of divine salvation but about a human psychological experience of trust and freedom from anxiety, guilt, and boredom.”7 He began a career as a liberal theologian until he began teaching at Drew University in 1970.8

It was there he met a new mentor, Will Herberg. Herberg was a Jewish Russian who had been an active member of the American Communist Party in the 1930s. He eventually left the party over disagreements with its Soviet leadership at the time and remained an independent communist until 1939 when he became disillusioned by the Hitler-Stalin pact. The experience led him to rediscover his Jewish roots and challenge Oden to do the same with his Christian roots.9

Paleo-Orthodoxy

The turning moment for Oden came when Herberg told him, “you will remain theologically uneducated until you study carefully Athanasius, Augustine and Aquinas!”10 Herberg insisted Oden get in touch with his Christian roots by examining the classical exegetes of the first five centuries of the church. His subsequent reading radically transformed Oden’s worldview. The political agenda of his youth vanished from his writing as he increasingly began working on what he called paleo-orthodoxy, which he defined as “the orthodoxy that holds steadfast to classic consensual teaching.”11

For Oden, classical Christian teaching fulfilled the inclusivity he worked to achieve as a Marxist political organizer because, while modernists maintain a bias against anything premodern, paleo-orthodoxy includes the wide scope of history across the globe within its consensus.12 But that is not to say he merely found a reflection of his political views in these writers.

On the contrary, in Clement of Rome and Gregory of Nyssa, Oden found the defeat of Nietzschian narcissism by God’s ultimate power over the human agency.13 In Gregory the Great’s pastoral teaching, Freud was defeated by an ancient Christian wisdom Oden found be far more holistic.14 In John of Damascus’ doctrine of divine providence, he found an economy more compelling than Marx’s doctrine of class struggle.15 Oden came to criticize his former ideologies. He accused Marxism of leading to totalitarianism, Freudian sexual liberation of the breakup of a moral framework for family, and Nietzschian nihilism of leaving a trail of genocide in its wake.16

Oden became a powerful anti-Communist voice, but to call him a mere convert to political conservatism would do a disservice to the nuance of his views. Indeed, he criticized our contemporary political spectrum as being two different versions of idolatry. One an idolatry of individualism, and the other an idolatry of collectivism.17

For Oden, the problem was never about mere politics, but rather a post-Enlightenment modernity, characterized by a kind of chauvinism toward the received wisdom of the past.18 This chauvinism had led him to read the past backwards, through a materialist and critical, modern lens.19 Despite all this, Oden’s paleo-orthodoxy was an optimistic one. In his role as a teacher of theology, he found a surprising delight in his students, upon a fresh reading of the Christian classics.20

The Paleo Influence of Missiological Theology

Michael T. Cooper was himself one of those enthusiastic students in Oden’s classes.21 In his work on missiological theology, he has said that “any movement toward a future missiological agenda would be deficient if it did not include history,”22 and indeed, this history permeates his writing.

His missiological theology looks to Vincent of Lérins for the boundaries of belief.23 Namely, his assertion to hold to what is “believed everywhere, all the time, by everyone.”24 For its engagement with the Missio Dei, it looks to Justin Martyr’s logos spermatikos25 in order to identify and make explicit what God is doing implicitly within a culture.26 Missiological theology blends the logos spermatikos with John of Damascus27 and Gregory of Nazianus’28 interpretation of the Trinity as perichoresis In doing so, it understands the Missio Dei as a perichoretic mission, engaging in a dance of catalytic, analytic, and cathartic dialogue with culture that mirrors the inward relationship of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.29

The influence of classical Christian orthodoxy via Oden is evident in missiological theology. It reflects Oden's assertion that paleo-orthodoxy is appropriate for missions because of its embracing of a multiculturalism rooted in Divine revelation than modernist relativism.30 Indeed, the consensual theology of the first five centuries is the only theology that has proved itself to be cross-culturally agile, crossing cultural barriers and persisting for millennia.31

But Oden is not the only advocate for a classical influence on missiological theology. Paleo-orthodoxy is, after all, situated in a critique of modernism’s diminishing of spiritual roots.32 This naturally introduces a question of identity into the conversation. To answer it, Nigerian theologian Kwame Bediako also looks to the classic roots of Christian belief. In his quest to articulate an African theological identity, he cites Tertullian’s assertion that Christians are made, not born.33 He argues this assertion constitutes a radical self-identity for believers.34

Cooper cites Bediako in his effort to learn from the early church’s engagement with paganism in light of the postmodern neo-paganism of today.35 He goes on to propose a theory of identity, satisfaction, and deprivation in his study of contemporary Druidry.36 He further develops the discovery Bible study formula commonly used in church planting movements into a framework for identity-based discipleship.37

Conclusion

As previously stated, doing theology in a cross-cultural setting runs a dual risk. On the one hand, syncretism with cultural practices can lead to heresy. On the other, the exporting of theological ideas unchanged can exacerbate neo-colonialism and replicate Western divisions in foreign churches. Missiological theology balances on the knife’s edge of cultural engagement by affirming a paleo-orthodox boundary for a theology developed in the creeds of the first five centuries that is culturally adaptive, yet globally and historically consensual.

This may naturally bring questions about the result of missiological theology. If the historic roots of Christian faith are unchanged, what does change, and how? The next article will focus on the “who” of missiological theology by examining its adaptive ecclesiology, as well as more biographical detail on Cooper’s journey towards developing missiological theology.

Bonnie Kristian, A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What it Means to Follow Jesus Today (Nashville, TN: Faithwords, 2018) 1.

Ibid, 2.

Roland Allen, Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours? (New Delhi: Grapevine India Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2023) 138.

Michael T. Cooper, Ephesiology: A Study of the Ephesian Movement (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Publishing, 2020) 118.

Thomas C. Oden, A Change of Heart: A Personal and Theological Memoir (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2014) 30-32.

Ibid, 42.

Ibid, 86.

Ibid, 132.

Ibid, 134.

Ibid, 136.

Tomas C. Oden, The Rebirth of Orthodoxy: Signs of New Life in Christianity (San Fransisco, CA: Harper San Fransisco, 2003) 34.

Ibid, 87.

Thomas C. Oden, The Living God: Systematic Theology: Volume One (New York, NY: Harper and Row Publishers, 1987) 76.

Oden, A Change, 142.

Oden, The Living, 270-273.

Oden, The Rebirth, 8.

Thomas C. Oden, Two Worlds: Notes on the Death of Modernity in America and Russia (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1992) 12.

Oden, The Rebirth, 8.

Ibid, 144.

Thomas C. Oden, After Modernity… What?: Agenda for Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Books, 1990) 14.

Michael T. Cooper, Ephesiology: A Study of the Ephesian Movement (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2020) 118.

Michael T. Cooper, “A Postmodern Counter-Culture: Christian Ancestors and Neo-Pagans,” in Sacred Tribes Journal 2, no. 2 (2005) 28.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 118.

Vincent of Lérins, Commonitorium, ch. 2.

Justin Martyr, Second Apology, ch. 8.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 90.

John of Damascus, An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, 1.14.

Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration, XL.XLI.

Michael T. Cooper, Innovative Disruption: Discovering Solutions by Reorienting the Church to a Trinitarian Mission, forthcoming, 26-27.

Oden, The Rebirth, 33.

Ibid, 41.

Oden, After Modernity, 16.

Tertullian, Apologeticum, 15.4.

Kwame Bediako, Theology and Identity: The Impact of Culture upon Christian Thought in the Second Century and in Modern Africa. (Oxford, UK: Regnum Books, 1999) 104.

Cooper, “A Postmodern", 28.

Michael T. Cooper, “The Roles of Nature, Deities, and Ancestors in Constructing Religious Identity in Contemporary Druidry" in The Pomegranate 11, no. 1 (2009) 63-65.

Michael T. Cooper, “Identity Based Discipleship,” Ephesiology Masterclasses, accessed June 9th, 2025, https://ephesiology.com/identity-based-discipleship/