As I work on the literature review for my dissertation, I am examining Missiological Theology as a framework indigenous expressions of church as a movement. I will be posting reflections on my readings here, as a form of pre-writing. This post represents one in that series of reflections.

Last year, while working on an ethnography of Mauritian Christians, I interviewed two young women about their experiences in the church. One of them attended an Anglican church and the other an Assemblies of God. I enjoyed sitting with them in the school where they worked. The little concrete building caught the island breeze and rustled some papers on a humid summer day. The two of them flashed a bright smile that I have come to know Mauritians for as we chatted about their experiences.

“Last year I went to a wedding course,” said the woman who attends AOG. “But to her church, it was in her church. It was very nice. But I didn't tell my parents because I knew their answers and it have been very difficult. So I'm not allowed to join others and to participate…”

She looked down and trailed off a bit. The other piped in to fill the silence.

“My parents always told me,” began the Anglican. “When you choose someone, choose someone who loves God. And so when I met my partner, we were best friends in school. He was a Catholic. So it was really challenging for us. Before announcing that to our parents, because on his side as well, they had bad experiences with family members married to people from Pentecostal churches. And they said, ‘We don't want you to come in our churches being like that.’ Yeah. So we were hurt by those words and it was difficult for us both.”

I was struck by the juxtaposition. These two women had such a warm way of interacting with each other. It was clear they were close friends. Yet, their different denominations created such a rift. I was grateful for their time and honesty.

Anglicans and Pentecostals are, of course, two church traditions that have their roots in the West. As previously mentioned, this calls to mind Roland Allen’s warning that Western dependence in missionary-planted churches runs the risk of reproducing Western schisms on foreign soil.1 In our neo-colonial setting, missionaries may find it difficult to plant churches if they are not sufficiently rooted in their cultures. It is this problem that led Michael T. Cooper to begin his work on missiological theology…

An Ephesian Epiphany

Cooper’s journey began in 1980, when he encountered Christ as a highschool student through the ministry of Cru. He would continue on with the organization through his undergraduate years, eventually becoming a member of its staff. In 1990, when the Iron Curtain lifted, he became one of the first Western church planters in post-Soviet Romania. He went out with a copy of Robert Logan’s book, Beyond Church Growth,2 where he learned many of the same principles used in DMM/CPM today, such as disciple making3 and expanding a network of small Christian communities.4

From 1990 to 1995, seven streams of multiplying churches were catalyzed in the former Communist nation.5 The next season of life proved difficult for Cooper and his wife Loré, as they experienced reverse culture shock upon returning to the United States, but they attended an Orthodox church, where they felt more at home. They returned to Romania and continued their church planting work for four more years, before returning to enter seminary at Columbia.6

Though he was planting evangelical churches overseas, his fond experiences with the Orthodox church led him to focus his studies on the early church fathers and the growth of the church after the New Testament period. Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, however, increasingly became of interest as well.7 Upon entering into the PhD program at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School,8 he wrote a dissertation on contemporary Druidry in the West, which, more broadly, helped build a deeper understanding of religious movements in general and how they grow.9

Meanwhile, he noticed that the church planting movement he had been a part of in Romania was not the only religious movement growing quickly. In the void left by the USSR, many new religious groups, such as the Mormons, Jehovah’s Witness, and Bahai were growing quickly as well. Eventually the reproducing churches he had been a part of began to dissipate due to American cultural influences. “Some of the new churches began to become attractional; after all, ‘attractional church’ was the new fad that seemed to be working in the States in the 1990s.”10

The experience as a church planter, study of the early church, interest in contemporary religious movements, and witness to neo-colonial interference on the mission field all came together when he published Ephesiology in 2020, which he called a book “twenty-five years in the making.”11 In it, he most clearly articulates what he came to call missiological theology, and continues to do so in subsequent works. Additionally, he established the Ephesiology Masterclass program, an online, decentralized seminary program which offers masters and doctoral degrees in missiological theology and a range of other topics relevant to missiology and movements (of which I am currently a student).12

Christlike Ekklesia

In many ways, Cooper’s missiological theology is born out of years of wrestling with the church. In the prologue of the forthcoming Innovative Disruption, he shares vulnerably about his commitment to the bride of Christ, despite a feeling of remorse over its blemishes that make it unattractive to the lost.13

Missiological theology sees the church as a movement called to be perfectly at home within a culture, yet perfectly faithful to a gospel that puts it out of step with society.14 It agrees with Lesslie Newbigin that the church should be a living hermeneutic in a pluralistic world,15 but it attempts to derive its ecclesiology from a missiology that is in turn shaped by its christology.16

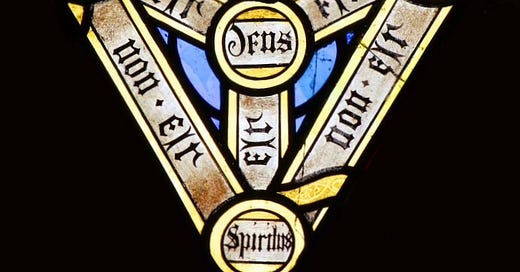

Synthesizing the wisdom of Gregory of Nazianzus, John of Damascus, Justin Martyr, and Athanasius of Alexandria,17 missiological theology attempts to recover a christology of God’s self-revelation, rooted in the perichoresis of a social Trinity. Such a Trinitarian theology sees the Godhead’s relational, interconnected love mirrored implicitly in culture. Christ then becomes the incarnation of that self-revelation by entering into a particular18 culture, glorifying God in ways people could understand, caring for them in ways that were relevant, and challenging them to turn from false worship.19 The church, then, as Christ’s body, should continue his work by fufilling three vital functions in society:

The analytic function, which observes and understands culture, engaging in respectful dialogue.

The catalytic function, which engages community as sent ones, pioneering new churches and making disciples.

The cathartic function, which facilitates the love and unity of the church, administering the Word and Sacraments.20

Furthermore, Ephesians 4:11 suggests that spiritual gifts were given to the church by Christ Himself, suggesting they, too, reflect a part of his incarnational nature. Thus, the prophets and teachers equip the church for the analytic function, apostles and evangelists for the catalytic, and shepherds for the cathartic.21

Learning from the Early Church

So far, we have addressed highly abstract chronological and ecclesiological concepts, but what do they mean, practically, for the church? We can look to history for examples.

Paul’s use of the Greek word ekklesia was unique. Originally meaning the assembly, it was borrowed from a common practice in the First Century, whereby citizens of a Greek city were called out to form a temporary decision-making body.22 Nowhere in any known ancient Greek literature is the word ever used to describe anything other than a temporary meeting of people, except in Paul’s writing. In contrast, he uses the word as a permanent marker of identity designated to all followers of Jesus, whether they were gathered together or not.23

When they were gathered, however, they borrowed structures of meeting and faith expression from the cultures from which they were called. Wayne Meeks lists the synagogue, the household, the voluntary association, and the philosophical school as models for the early church.24 These models, according to the New Testament, seemed to be more pronounced according to the cultural context of a given church. In Jerusalem, for example, believers attended Jewish worship in the temple.25 Their communal support for one another26 resembled the synagogue.27 Meanwhile, the church in Ephesus at one point resembled a philosophical school.28 Leadership structures looked different across the Jesus movement, as well. In Philippi, for example, there were bishops and deacons,29 while in Jerusalem there were elders.30

Larry Hurtado catalogues the ways in which churches adapted cultural forms while remaining distinct in their emphatic rejection of idols.31 Their practice of the Lord’s supper resembled the ritual meals of voluntary associations, yet abstained from foods sacrificed to idols. In this way they situated Christ as a kyrios familiar to the culture, and yet maintained his unique universality by rejecting all else.32 Similarly, baptism bore striking resemblance to the ritual washing of mystery cults, but stood over and against them as a one-time rite of initiation, forfeiting the cultural practice of honoring other gods through repeated cleansing.33

The early Jesus movement also appealed prophetically to its various settings in its presentation of Christ. Most scholars agree that Matthew most likely wrote his gospel before the the Jewish War, in a mixed community primarily of diasporic Jews cut off from their roots, but Gentiles as well.34 Matthew reaffirms the Jewish identity of his community by meticulously connecting Jesus to the promised Messiah. He fulfills Isaiah’s prophecy through His virgin birth,35 Micah’s prophecy of Bethlehem as His birthplace,36 and Hosea’s prophecy that like Moses He would be called out of Egypt.37

At the same time, Matthew encourages unity by slowly conditioning his Jewish readers towards accepting their Gentile brothers and sisters.38 Wise men of the East arrive to worship the Messiah,39 and a Canaanite woman impresses a reluctant Jesus with her faith.40 Christ even marvels at a Roman centurion, saying, “I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith!”41 Matthew maintains his Jewish audience’s expectations by casting Jesus as an itinerant rabbi exclusively ministering to Jews. Yet he encourages unity with Gentiles by recounting how they came to Him and He never turned them away. This of course culminates in the conclusion of Matthew’s gospel, with the commission to make disciples of all nations.42

John, however, writes to a mainly Gentile audience in Ephesus and Asia Minor. Assuming he arrived in the city during the beginning of the Jewish War, the temple in Jerusalem would not yet have been destroyed.43 It is reasonable, then, to assume that his depiction of Jesus clearing the temple44 is meant to call to mind the Temple of Artemis, by far the most important land mark of the region, which would have been filled with various idol craftsmen and sellers of religious goods. Ephesus was also an important location for the philosopher Heraclitus, whose philosophy of the unchanging logos would have been well known.45 John opens his gospel by identifying Jesus in this language.46

He goes on to tell many true stories of Jesus that would have connected deeply with Ephesian culture. His ministry opens with a miracle at a wedding,47 which would have evoked the imagination of worshippers of Artemis, goddess of matrimony. It includes a call to be born again,48 reminiscent of Dionysius, who was twice born of Zeus. Even foot-washing49 was a common occurrence in Ephesus, with which his audience would surely have related.50

Conclusion

These examples simply illustrate missiological theology’s adaptive ecclesiology, which takes the form of a living system51 borrowing from the culture without sacrificing its universality and commitment to Christ. Looking around the world today, we find this is largely not the case. Years of captivity by Western culture and the colonial era have exported models of church that repeat the styles of American and European denominations, despite the good intentions of many. Missiological theology encourages the kind of theocentric, perichoretic mission that promises to plant churches capable of articulating theology and expressions of doctrinally faithful belief and practice using local vernacular and resources, whether they be in Asia Minor, America, Romania, or Mauritius.

Roland Allen, Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours? (New Delhi: Grapevine India Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2023) 138.

Michael T. Cooper, Ephesiology: A Study of the Ephesian Movement (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2020) 16.

Robert E. Logan, Beyond Church Growth (Old Tappan, N.J.: F.H. Revell, 1989) 94.

Ibid, 118.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 17.

Michael Cooper, Innovative Disruption (forthcoming) 7.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 17.

Cooper, Innovative, 8.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 17.

Cooper, Ephesiology, 272.

Ibid, 18.

“Ephesiology Master Classes,” Ephesiology, accessed June 13, 2025, https://ephesiology.com/master-classes/

Cooper, Innovative, 8-9.

Andrew F. Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2009.) Chapter 1.

Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989) 237.

Alan Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways Reactivating Apostolic Movements (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016) 226.

Cooper, Innovative, 26-32.

Stephen B. Bevans, Models of Contextual Theology (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2002) Chapter 1.

Cooper, Innovative, 19.

Ibid, 21.

Ibid.

Everett Ferguson, The Church of Christ: A Biblical Ecclesiology for Today (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996) 131.

Ralph J. Korner, The Origin and Meaning of Ekklesia in the Early Jesus Movement (Boston, MA: Brill, 2017) 12.

Wayne Meeks, The First Urban Christians : The Social World of the Apostle Paul (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983) 75-84.

Acts 2:46 (NIV)

Acts 4:32 (NIV)

Lee Levine, The Ancient Synagogue : The First Thousand Years. 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005) 396-398.

Acts 19:9 (NIV)

Phil. 1:1 (NIV)

James 5:14 (NIV)

Larry W. Hurtado, Destroyer of the Gods : Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World. (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2016) 44.

Ibid, 60-61.

Ibid, 59.

David Bosch, Transforming Mission : Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011) “Matthew and his Community.”

Matt 1:23 (NIV)

Matt 2:5-6 (NIV)

Matt 2:15 (NIV)

Bosch, Transforming, “Contradictions in Matthew.”

Matt 2:1 (NIV)

Matt 15:21-28 (NIV)

Matt 8:10 (NIV)

Matt 28:18-20 (NIV)

Cooper, Ephesiology, 143.

John 2:13-17 (NIV)

T.M. Robinson, Heraclitus: Fragments (University of Toronto Press, 1987)

John 1:1 (NIV)

John 2:1 (NIV)

John 3:1-15 (NIV)

John 13:5 (NIV)

Michael T. Cooper, “John’s Missiological Theology: The Contribution of the Fourth Gospel to the First-Century Movement in Roman Asia” in Motus Dei: The Movement of God to Disciple the Nations, ed. Warrick Farah et al. (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2021) 169.

Hirsch, Forgotten, 311-312.