There may be an article on missiological theology been hidden in one of the most popular children’s books series.

It can be found in chapter fifteen of The Last Battle, book seven of C. S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia. In the midst of this closing episode of Lewis’ epic narrative, there are two moments which take a surprisingly missiological turn and sound like they could have been inspired by the church fathers.

First, a Calormene shows up in Naria’s version of Heaven. For those who have not read the book, Calormenes are a desert-dwelling people who come from the south and hate the Narnians. More specifically, they hate Aslan, the stand-in for Christ in the book series. So it is surprising when a servant of the evil god Tash appears in Narnia’s imaginative version of the afterlife when the dust of the eponymous last battle settles. He tells the protagonists, “I have served Tash and my great desire was to know more of him and, if it might be, to look upon his face. But the name of Aslan was hateful to me.”1

Perhaps some evangelicals might be surprised to hear Lewis—a beloved author among evangelicals—suggest through story what is essentially a pagan become saved despite never having encountered “Christ.” They may question Lewis’ orthodoxy. Yet, Lewis is right in league with the very clarifiers of orthodoxy on this point! Clement of Alexandria believed that Greek philosophy was an instrument of God to bring the Greeks to Christ in the same way He used the Law to bring Jewish believers to Him.2 Origen believed pagans philosophers like Plato were inspired by God.3 Most strikingly, Justin Martyr considered the great pagan philosophers to be a kind of proto-Christian.4

Lewis goes to great lengths to depict the Calormene in Narnia as an honorable pagan, whose devotion to Tash is credited to him as devotion to Aslan. Oxford classicist and storyteller that he is, Lewis asks his readers to consider whether all the inside stuff of a non-believer could potentially be the same as a Christian. In essence, they just got the name wrong. While not all the patristics agreed on this point,5 many of them at least suggested that this might be possible.

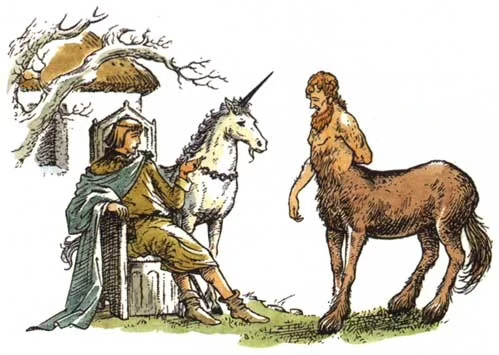

The other surprising missiological point that appears in chapter fifteen of The Last Battle, is when Jewel the unicorn, overcome with emotion upon seeing Aslan’s country, stamps his hooves and cries:

I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now. The reason why we loved the old Narnia is that it sometimes looked a little like this. Bree-hee-hee! Come further up, come further in!6

This again seems to take inspiration from church fathers. It calls to mind Gregory of Nyssa’s idea of epektasis, which describes the journey of the soul into the Divine as a passionate never-ending journey further into His goodness and perfection.7 While this does not at once seem overtly missiological, it may contain theological implications for our engagement with the missio dei and motus dei, which will be explored below.

Previous articles have focused on the importance of including the exegetes of the first five centuries into the hermeneutical community of missiological theology. But, so far we have yet to explore these voices in detail and let them speak for themselves. This article will focus on what these patristics had to say about missiological topics.

Logos Spermatikos

The book of Genesis depicts the Spirit of God hovering intimately over the waters.8 Each time God creates something, he calls it “good,” until he creates humankind, and calls it “very good.”9 In the New Testament, we see the resurrected Jesus still with holes in his hands10 and Peter finds him on a shore cooking and eating fish.11 What ties all these seemingly disparate Bible verses together is the inherent goodness of the physical world.

It is this goodness that Irenaeus of Lyon argues for in his treatise, Against Heresies. In the Second Century, among the most prolific of heterodox groups were the Gnostics, who believed that the physical world is an aberration created by misguided spiritual beings, and to attain salvation was to gain a secret spiritual knowledge. According to Irenaeus, the Gnostics were fond of appropriating the accounts of Jesus and suggesting there was hidden Gnostic knowledge within them.12 Instead, he affirms the goodness of creation,13 but also argues for Christ’s intimate involvement in salvation history, ultimately saying that “all other things, and all human affairs, are arranged according to God the Father's disposal.”14

This working of God through all human affairs is integral to Justin Martyr’s logos spermatikos. A phrase later attributed to his ideas, it means seeds of the Word. For Justin Martyr, God revealed in Christ has been present and active in the world and human cultures throughout history.15 We see this at work in the life and writings of Paul. He argues in Romans that God’s “eternal power and divine nature have been clearly seen” by people of all nations. This means they are accountable to their turning away from Him, most potently in the act of idolatry,16 but it also implies there is something of God in all cultures. Paul demonstrates this in Athens, when he recognizes the desire God had placed within them, highlighting the alter to the unknown god, and quoting from their own religious poetry.17

Arguably, the most important concept in missions discourse today has been the missio dei, which suggests that the mission of revealing God to all peoples belongs to God, not us. If that is true, then we must realize that He is not dependent on us to do so. Though He works in and through the church as the body of Christ on Earth, this does not mean he is not at work within non-Christian cultures. This understanding transforms the missionary task from one of domination, coming to impart our own version of truth to a pitiable people, to a task defined by a joyful discovery of the things God is doing within a cherished people, and then partnering with Him in His work.

Perichoretic Mission

Much of the church fathers’ writing can be summed up in the development of Christology and the doctrine of the Trinity. Few offer a better picture of this than Athanasius’ crusade against Arianism. The Arians believed in a subordination of the Son to the Father, but Athanasius successfully argued for Christ’s equality with the Father by connecting His incarnation to our salvation.18 In the introduction to this argument, he depicts a Christ so moved by his love for us, that He descends to reach us:

…our own transgression evoked the Word’s love for human beings, so that the Lord both came to us and appeared among human beings. For we were the purpose of his embodiment, and for our salvation he so loved human beings as to come to be and appear in a human body.19

This movement in the Godhead laid the foundations for Gregory of Nanzianus’ beautiful description of the Trinity as a kind of dance-like interrelation between the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit.20 John of Damascus would later call this a mutual indwelling,21 which came to be known as perichoresis, a Greek term meaning “to move around.”

Harkening back to Athanasius, the movement of perichoresis is a sending of the Son by the Father and the procession of the Holy Spirit thereafter. Michael T. Cooper connects the eternal self-sending of God with the motus dei,22 which describes God as a God of movement.23 Mission, then becomes a perichoretic mission, in which the church mirrors God’s constant self-sending.

The church wasn’t meant to be static. It should always be on the move, sending itself motivated by love, just as God constantly sends Himself out of His love. To suggest the Church fathers were proponents of Church Planting Movements would, of course, be anachronistic. CPM methodology emerged in the modern day out of a need to call the post-Christendom church back to its nature as an organic movement. The early church had no need to shake off years of Western captivity. Their focus was more on clarifying the nature of God, so that they could better proclaim Him to the nations. The natural outworking of their theology was a rapid multiplication of churches that we might call a CPM today.

Epektasis

If we are to say God is a God of movement, and if we are to say that mission is an attribute of God, then what implications does this have for the afterlife? Since God is the same yesterday, today, and forever,24 then any attributes we see within Him today must also be true in eternity. Origen states that while God is dynamic, He is unchanging, and cannot be said to have added or removed anything from His nature.25 If all people in Heaven are “reached,” then what of His missional qualities?

Gregory of Nyssa offers an answer to this conundrum. In his commentary on the life of Moses, he says:

The nature of the Good attracts to itself those who look to it, the soul rises ever higher and will always make its flight yet higher—by its desire of the heavenly things straining ahead for what is still to come.26

The word he uses for straining is the same word Paul uses in Philippians 3:13-14 when he says, “forgetting what is behind, and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal…” That word is epektasis and it became foundational for Gregory’s model of the spiritual life, as the soul eternally strains ever higher for God.

This is not the same kind of striving commonly discussed in popular books such as Brennon Manning’s The Ragamuffin Gospel,27 which warns believers about the dangers of trying to earn God’s approval. Rather, Gregory’s epektasis is described as a kind of passionate love, which wounds but also heals us and draws us ever closer to God.28 It is because of God’s rich goodness that our souls are drawn to Him, and since His goodness is infinite, our passionate attraction to Him continues for all eternity. Like C. S. Lewis’ unicorn, we are drawn further up, and further in.

This solves our problem of the missio dei in heaven. If we understand the task of mission to be more than just our modern project of traveling the globe to plant churches, we might understand it to be God’s infinite self-revelation to His people. There is no reason, then, to assume this should stop in Heaven. God will continue His mission, wooing our hearts for all eternity, and we will never exhaust the riches of his love.

Our response to Him, then, is movement. Since we will be ever moving higher towards Him for all eternity, we can look at the modern missionary task as entering into Heaven, while still in this life. As we search the globe for what God is already doing to reveal Himself to the lost, our response, in love, is to participate with Him in that constant, divine movement. As the church emerges from this perichoretic mission and our response to it, it may look differently than what we have previously known. It may become an ekklesia of epektasis, moving ever onward, expanding and innovating in new ways to the cultures in which it finds itself.

Conclusion

I have attempted to show the “what” of missiological theology in this article by examining the work of the patristics through a missiological lens. Not only do these fathers of orthodoxy establish the boundaries for faithful theology, but they themselves provide a missiological theology that transforms our understanding of the missionary task.

But, I fear I have yet to properly demonstrate missiological theology here, as it is not best done in the context of one person writing. Rather, it should be done in community.29 For this reason, I hope to end this series of articles with a final post describing how to do missiological theology.

C. S. Lewis, The Last Battle (La Vergne: Dreamscape Media, 2018) 80.

Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 1.5

Origen of Alexandria, Contra Celsum 6.3

Justin Martyr, First Apology 6.3

See

Augustine of Hippo, City of God, 10.32

Lewis, Last, 84

Gregory of Nyssa, Homilies on the Song of Songs, 8.259

Genesis 1:2 (NIV)

Ibid, 1:31

Luke 24:39-40 (NIV)

John 21:10-14 (NIV)

Ireneaus, Against Heresies, I.1

Ibid, V.18.2

Ibid, V.22.2

Justin Martyr, First Apology, 46.

Romans 1:19-23 (NIV)

Acts 17:22-28 (NIV)

Athanasius of Alexandria, On the Incarnation, §54.

Ibid, §4

Gregory of Nanzianus, Oration, XL.41

John of Damascus, Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, I.8

Michael T. Cooper, Innovative Disruption (forthcoming) 28.

Warrick Farah, “Introduction” in Motus Dei: The Movement of God to Disciple the Nations ed. Warrick Farah et al. (Littleton, CO: William Carey Publishing, 2021) 25

Hebrews 13:8 (NIV)

Origen of Alexandria, On First Principles, I.1.6

Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, II.225

Brennan Manning, The Ragamuffin Gospel: Good News for the Bedraggled, Beat-Up, and Burnt Out (Colorado Springs, CO: Multnomah, 2005)

Gregory of Nyssa, Homilies on the Song of Songs, J.365

Granted, what I have shown in this article has been—to some extent—missiological theology, since it has been in dialogue with the community of history through the patristics. Still, missiological theology seeks to bring people of varying cultures and backgrounds together in order to expand the hermeneutical community.